John Surtees was a very great driver, and rider. As a person and at least to a hack asking questions he thought obvious or trite, he could be difficult. Curmudgeonly even; at times dismissive to the point where a more sensitive soul might consider him rude. I learned this the hard way when, at a Goodwood lunch I was sat next to him and asked him whom he considered to be the greatest driver of all time.

There was a long pause, I expect because he was considering whether such a stupid question even merited a reply, after which he explained somewhat tersely that there was no such person. How could you compare drivers from different eras facing different challenges in different environments using utterly different equipment?

And the most annoying thing about his reply was he was absolutely correct. So when the GOAT question raises its head these days, as it frequently has, it is always the Surtees line I take.

And once I’d learned not to ask him dumb questions, we actually got on quite well, and he was always prepared to give a considered and illuminating response to any sensible question you cared to ask. For instance I remember suggesting to him that Michael Schumacher was partly to blame for ramming David Coulthard’s dawdling car at a very wet Spa in ’98 and that the accident could have been easily avoided if he’d not been on the limit in a race he was already winning by miles.

“But the limit is the safest place to be in such circumstances,’ he replied. ‘Because that’s when you’re concentrating the most, and in most complete control of your car.”

A racer’s response if ever there were one.

But back to the GOAT argument. If it can’t be applied to people for reasons outlined above, what about cars?

I think the rules are rather different here, because the terms of reference are so very different. And here there is also a constant: it doesn’t matter if I’m driving a vintage Bentley or a brand new hypercar, I’m looking for the same thing: a capacity to engage, involve and excite, to communicate directly with whatever lies deep within the core of my brain that has led me to love cars for as long as I can remember. And there is a simple measure too, far more reliable than totting up race wins or world championships and it is simply this: if, for whatever reason, you could have one last drive in one last car, what would it be?

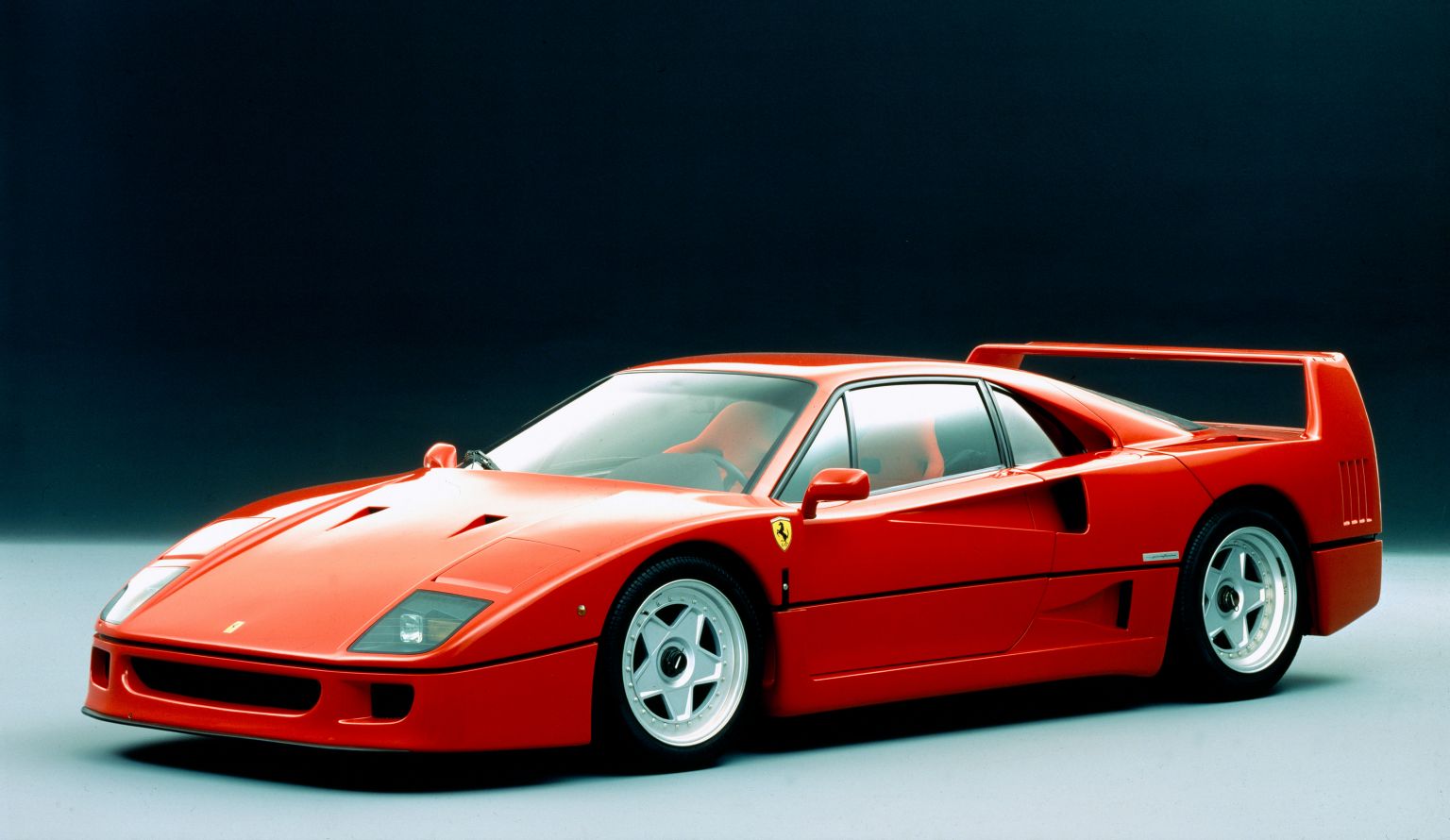

And to me the answer has always been the same: the Ferrari F40. Actually that’s not entirely true. When it first came out and Car magazine was my oracle, I read its slightly sniffy report on the car’s launch and concluded it wasn’t for me. More recently and briefly, I thought the LaFerrari might have eclipsed it too. But when the dust had settled and everything was back in its natural state, every time I asked myself that last blast question, the answer was always the same: F40.

I’d like to say it was for purist reasons, because this was Enzo’s last car, but the truth is he was an elderly and ailing man at the time of its creation, though I always admired the one public pronouncement I am aware of him making about the car. Not a man for the carefully constructed, on-message press release, he said simply that it was ‘so fast you’ll shit yourself.’

But it’s got nothing to do with that. Nor is it because at the time I’d never driven anything that rapid. I had. Because even if there had been an F40 lying around the Autocar offices when it was new in the late Eighties I’d have had more chance of winning Miss World than being allowed to drive it. In fact it wasn’t until the early Nineties that I first made my acquaintance with a car that had by that time been out of production for a few years; and by then I’d already driven the Jaguar XJ220 whose raw pace eclipsed that of the Ferrari entirely.

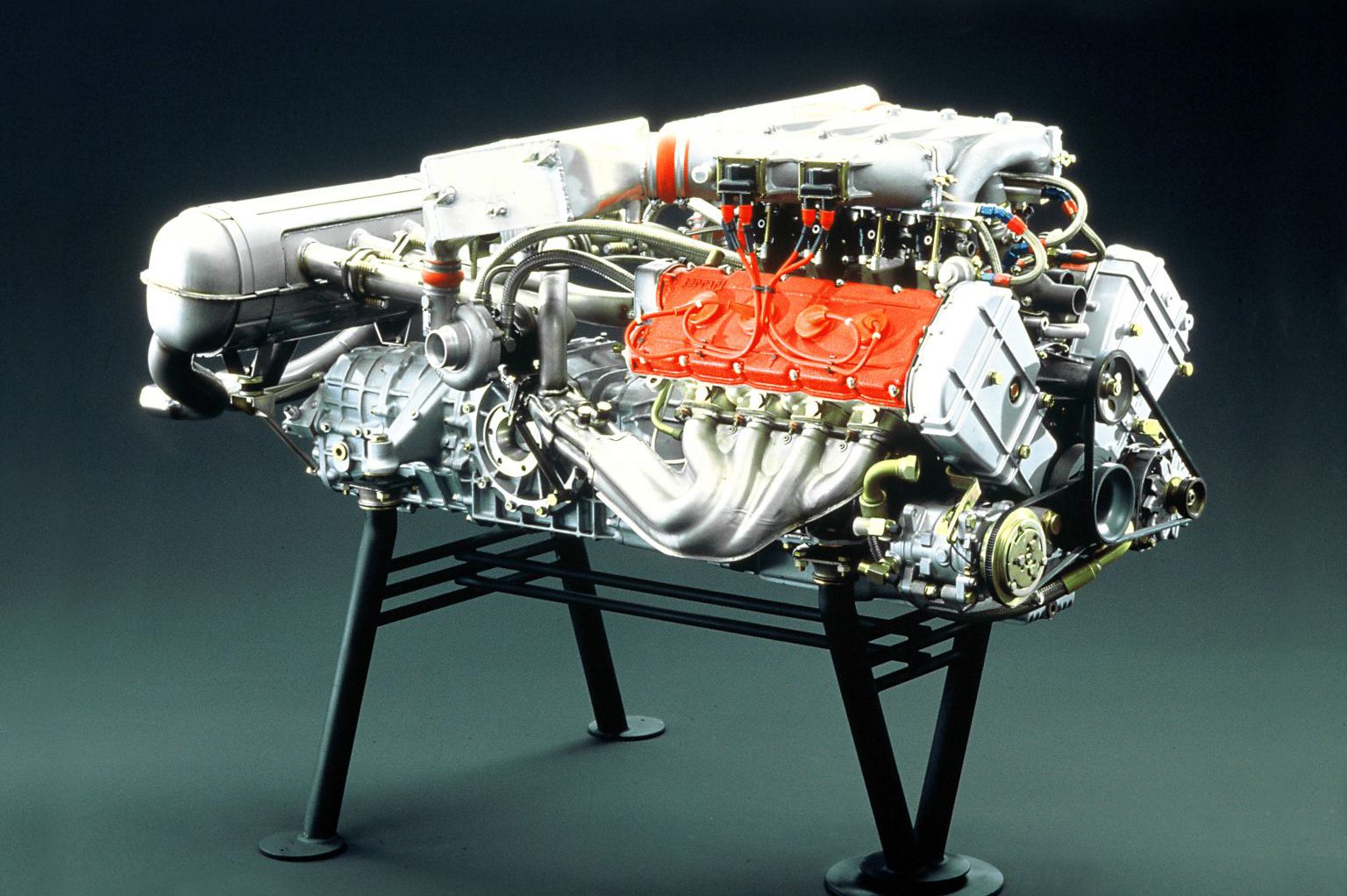

Nor is it because it’s so classically configured because, being blunt, it isn’t. To this day I find it curious that the greatest road car I’ve ever driven doesn’t have a naturally aspirated V12 under its bonnet, but a twin-turbo V8 mounted behind the driver.

This article is brought to you by The Intercooler, a groundbreaking digital car magazine with which we are proud to be partnering. Watch our Fund Your Passion podcast with Andrew Frankel and Dan Prosser here.

So what is it? I can express it in emotional terms very easily. I must have driven five or six F40s and there is nothing more capable of making me feel like a schoolboy again than knowing there’s a drive in the diary. There have been cars with quadruple digit power outputs which have not troubled my sleep pattern the night before. But there is nothing entitled to wear a number plate more likely to induce insomnia than an F40.

The most recent was a couple of years back when I borrowed a very trusting customer’s car from Bob Houghton. And for the first five minutes I just stood there looking at it on Bob’s forecourt, scarcely believing it was mine for the day. Then I spent at least as long sitting in it and giggling. Pathetic, really. And on this occasion as with all previous, when I’ve handed it back, it was only with thoughts of what if this was the final time? What if this were my last F40? And there’s never anyone around to provide what I need at times of such deep emotional crisis: namely a slap around the face and to tell me what an appallingly spoiled and entitled arse I have become.

That, then, is the effect the F40 has on me. But I have not yet explained why. I have said many times before that the cars I love most are those that know what they are for, and the formula works as well whether it is an original Fiat 500, a Series Land Rover or a Ferrari F40 under discussion. The F40’s purpose is simply to make your heart soar, even at the risk of inducing myocardial infarction. It starts with the look. I know that few reading this will have been lucky enough to travel in an F40, but if you look at it and imagine what it must be like, that is what it is like.

No car has ever fulfilled the promise of its appearance more accurately than this.

Inside there is a simplicity that makes a Porsche 911 GT3 RS look like a luxury SUV. There really is nothing in here. The simplest of binnacles with basic white on black instruments. A dash top covered in black felt. No carpets, no trim. String for door handles. And that’s it. What’s left is the simplest Momo steering wheel with the horse in yolk motif at its centre. To your right, the black ball on a steel shaft descending to an open gate. The very essence of Ferrari.

Press a simple rubber button and a racing engine designed for Lancia to win the World Sportscar Championship clatters into life. It’s difficult to drive and I love that too. You can’t see out the back, the engine is truculent off boost, the clutch is hideously heavy. You have to miss out second gear until the oil temperature gauge has lazily lifted off its stop.

You need 20 miles to get everything warm, which is hopefully enough to find the right road. When you do, and if you’ll forgive the technical term, the F40 just goes nuts. When those twin IHI turbos light up and thrust you forward it’s all you can do to not let laughter take over. You must instead concentrate on banging through the next change, because with maximum torque not available until 4000rpm and the redline at 7700rpm, there’s not much time between them.

But even when you have to lift there’s more joy because the motor fizzes, crackles, pops and bangs like the sky above Buckingham Palace on Jubilee night. And you’ve not even reached a corner yet. The brakes have no assistance at all. The only thing slowing you from whatever preposterous speed you’ve just reached are the group of quadricep muscles within your right thigh. And quite right too.

Drop a couple of gears, discover perfectly positioned pedals (heel and toeing is not negotiable when driving an F40 fast), then angle into the corner. It turns in flat and fast like a Caterham, but one with 478bhp. The steering is so alive you’d swear it was breathing. Through the chassis you can feel it’s trying hard, and yet there is no fear. Not yet at least. But here comes the big question. The apex is here. How hard do you squeeze? Just a little to maintain momentum? Because any more is going to wake up the IHIs, and for all their proven and mighty assets, subtlety is not among them. And do you really want a big, fat dose of torque to those rear wheels, guaranteed to wrench even a 335mm-wide Pirelli loose from the tarmac?

Of course you don’t. Except. Except that something in those miles has told you it’s going to be okay, that the only misleading thing about the appearance of this car is that when it really, really matters, when it letting you down has consequences that cannot be countenanced, it will remain loyal. So the question is, do you trust it? All other two seat Ferraris of that era did terrible things on the limit at far lower speeds; why should this be different? Because it’s an F40. So, and largely because you cannot bear to go home without discovering this final facet of this extraordinary car’s character, you squeeze harder.

And there it goes. The back is loose now and heading in the direction of Northamptonshire. The good news is there is no decision to be made, because the results of doing anything other than keeping your foot down and correcting with the steering are unlikely to be pretty. So you do, and that’s when you earn your freeze frame moment. An F40, slightly sideways, perhaps a lick of smoke curling out a rear arch, with you at the wheel.

And no you can’t see any of that, but nor do you need to, because you’re still inside, goggling at how good this car is, how something of which you were suspicious until that very moment had transformed instantly into your very best friend. Because the whispered truth is, in the dry at least, a well set up F40 is a pussy cat, there to indulge your wildest automotive fantasies to make you look, sound and feel like the hero you are so clearly not.

And nothing else has ever done that for me, at least not to the same extent. Why? I guess because it’s so light – barely more than a tonne and certainly less than a McLaren F1 – so raw and so focussed on the job in hand, to the almost total exclusion of anything else.

I won’t say it’s the best car I’ll ever drive, because there are some interesting candidates on the horizon; but in 34 years in this job, the truth is that the best road car I’ve driven wasn’t even a new car when I first drove it. And it will take something utterly spectacular to beat it.

Talk with us to

Want to fund your passion?

We at JBR Capital are experts in financing Super Cars, Classic Cars and High-end Prestige Cars. We are the UK's only independent high-end car financier, with advisors who can help with Hire Purchase and Lease Purchase on all sorts of marques. Ferraris, Porsche, Mercedes, Lamborghini and Range Rover are our specialities, but we cater for all manner of cars. We loan from £50k to £2million. Why not try out our Car Finance Calculator to see if you can Fund Your Passion.